What is Gender?

Gen·der - Noun

The range of characteristics pertaining to, and differentiating between, femininity and masculinity. Depending on the context, these characteristics may include biological sex, sex-based social structures (i.e., gender roles), or gender identity (the personal sense of one's own gender).

If you trace the etymology of the word to its Latin roots, gender simply means “type”. The Norman French term gendre was in use in the 12th century to describe “the quality of being male or female.”

Many people attribute the term to psychologist John Money, who proposed using “gender” in 1955 to differentiate mental sex from physical sex. However, Money was not the first to do so. Cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead used the term in 1949 in her book Male and Female to distinguish gendered behaviors and roles from biological sex. The American Journal of Psychology (vol. 63, no. 2, 1950, pp. 312) described the book thusly:

A book, moreover, which gives beyond its premise; for it informs the reader upon ‘gender’ as well as upon ‘sex,’ upon masculine and feminine roles as well as upon male and female and their reproductive functions.

Margaret Mead moves from the specific delineation to the more general comparison of male and female in several communities, finally coming to an analysis of sex-patterns in our own midst and for our own time.

Human Sex (the adjective, not the verb) is broken down into three categories:

- Genotype: The genetically-defined chromosomal kareotype of an organism (XX, XY, and all variants thereof)

- Phenotype: The observable primary and secondary sexual characteristics (genitals, fat and muscle distribution, bone structure, etc.)

- Gender: The unobservable sexual characteristics, the internal mental model of a person’s own sex, and the way that they express it.

Any of these three aspects can fall into a position on a range of values. Your elementary school health class probably taught you that genotype is binary, either female (XX) or male (XY), when the reality is that there are a dozen other permutations that can occur within human beings.

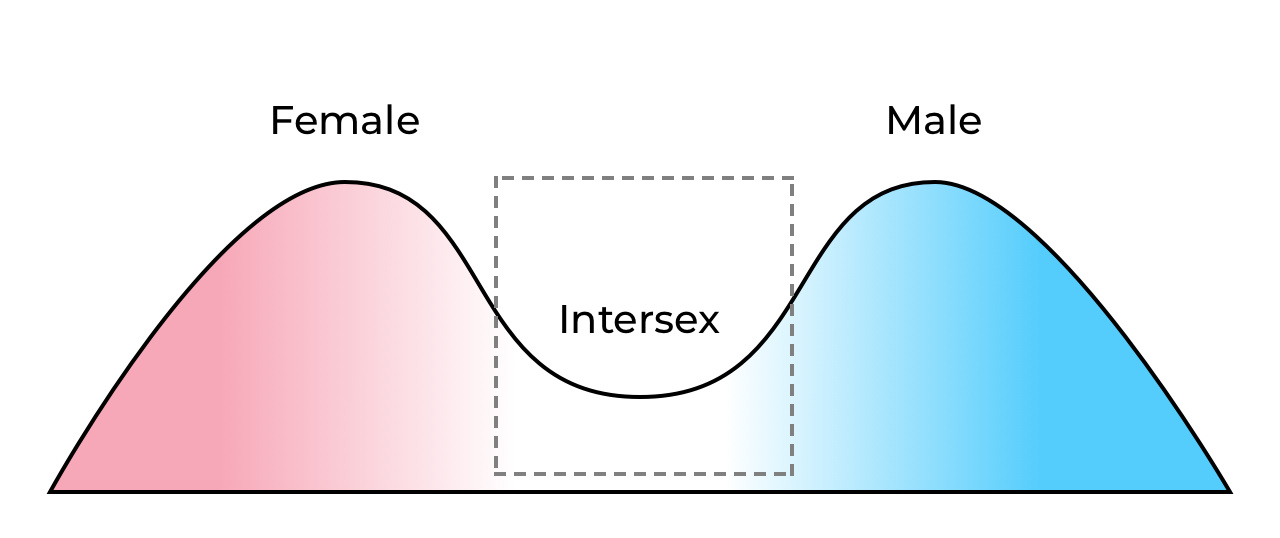

Likewise, many people believe that phenotype is also binary, but biology has recognized for hundreds of years that, when you plot out all sexual characteristics across a population, you actually end up with a bimodal distribution where the majority of the population falls within a percentile of two groups. This means that some people will, simply by nature of how life works, fall outside of the typical two piles. Many people fall in the middle, with characteristics of both sexes.

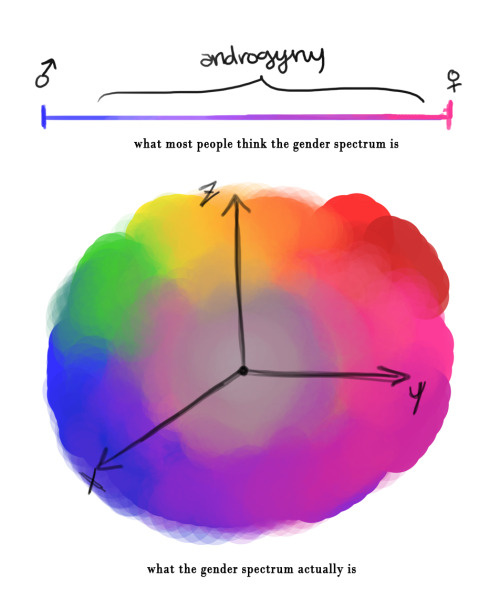

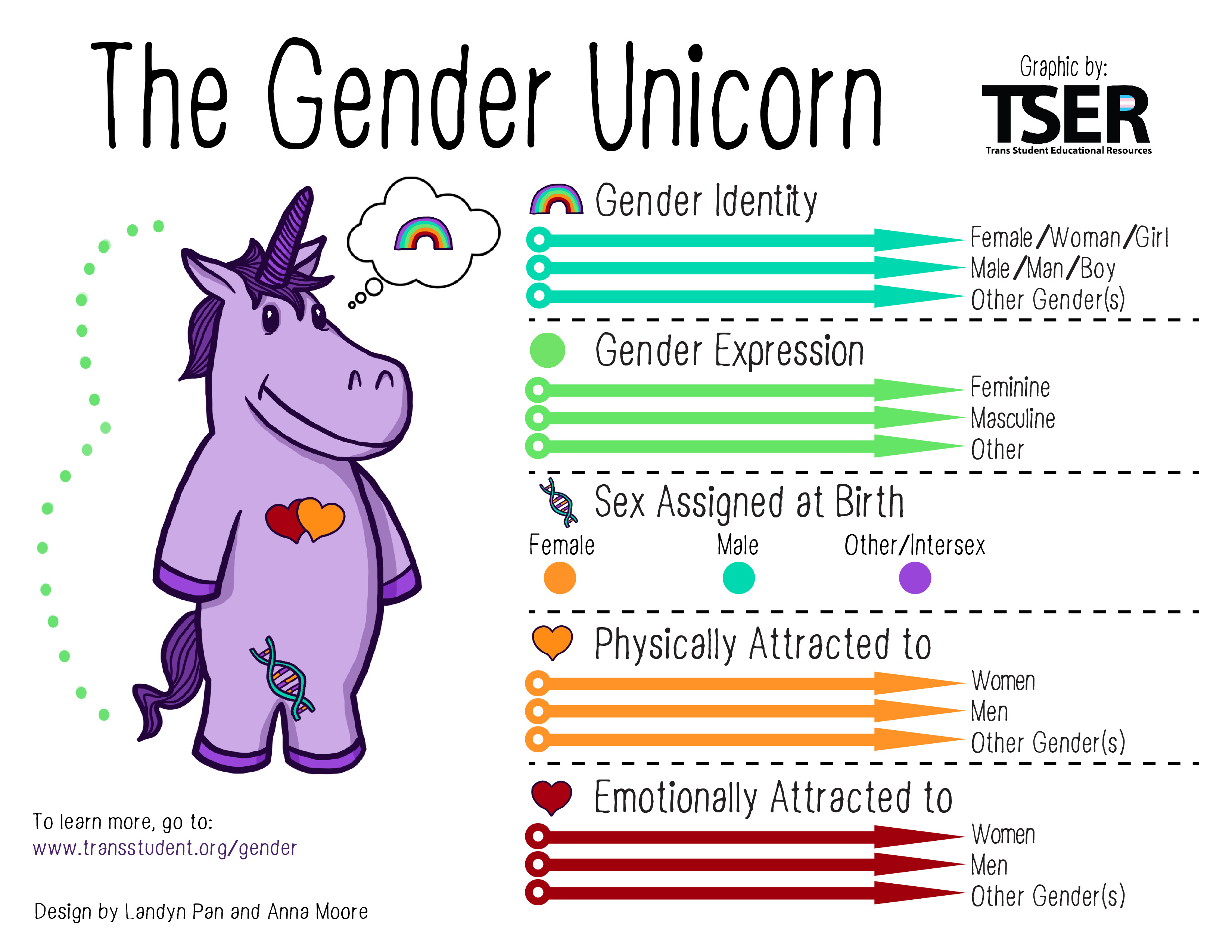

Gender, however, is a lot more… esoteric. There are a lot of different ways in which people have attempted to illustrate the gender spectrum, but none have quite thoroughly captured it because the spectrum is itself a very abstract concept.

The short of it is: some people are very male, some people are very female. Some people feel no gender at all, some people feel both. Some are smack in the middle, some land along the edges. Some people oscillate all over the spectrum in unpredictable ways, changing like the wind. Only an individual can identify their own gender; no one else can dictate it for them.

Gender is part social construct, part learned behaviors, and part biological processes which form very early in a person’s life.

Present evidence seems to suggest that a person’s gender is established during gestation while the cerebral cortex of the brain is forming (more about that in the Causes of Gender Dysphoria section). This mental model then informs, at a subconscious level, what aspects of the gender spectrum a person will lean towards. It affects behavior, perceptions of the world, the way we experience attraction (separate from sexual orientation and hormonal influences) and how we bond with other people.

Gender also affects the expectations that the brain has for the environment it resides in (your body), and when that environment does not meet those expectations, the brain sends up warning alarms in the form of depression, depersonalization, derealization, and dissociation. These are the brain’s subconscious ways of informing us that something is very wrong.

Hab·i·tus - Noun

Socially ingrained habits, skills, and dispositions. The way a person perceives and reacts to the world.

On the social side, gender involves our habitus: our presentation, our mannerisms and behaviors, how we communicate, how we react, what our expectations are from life, and the roles that we fulfill as we walk through life. The author Susan Stryker described habitus it in her book Transgender History:

A lot of habitus involves manipulating our secondary sex characteristics to communicate to others our own sense of who we feel we are—whether we sway our hips, talk with our hands, bulk up at the gym, grow out our hair, wearclothing with a neckline that emphasizes our cleavage, shave our armpits, allow stubble to be visible on our faces, or speak with a rising or falling inflection at the end of sentences. Often these ways of moving and styling have become so internalized that we think of them as natural even though—given that they are all things we’ve learned through observation and practice—they can be better understood as culturally acquired “second nature.”

Indeed, these are all cultural factors: things which have developed within the population over time. Regardless of being essentially “made up”, they are still strongly gendered and a person tends to connect to the gendered habitus of their internal self without even realizing they are doing it. When we are denied access to those social aspects, this results in discomfort with one’s social position in life.

John Money’s experiments attempted to confirm his belief that gender is entirely a social construct, and that any child can be raised to believe themselves to be whatever they were taught to be. His experiment was a massive failure (see the Biochemical Dysphoria section). Gender does not change; every human is the same gender at 40 that they were at 4. What changes is our own personal understanding of our gender as we mature as individuals.

These negative symptoms (depression, derealization, social discomfort) are the symptoms of Gender Dysphoria.

What Gender is not is sexual orientation. We describe orientation using terms relative to one’s gender (homosexual/heterosexual/bisexual, etc), but gender itself does not affect sexuality and sexuality has no role in gender.

What does it mean to be Non-binary?

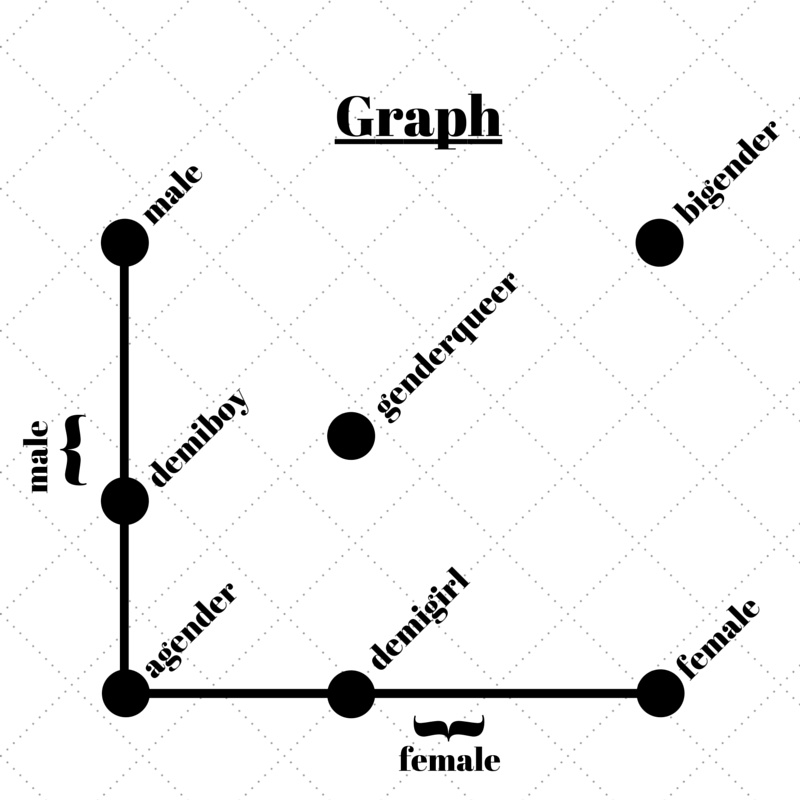

Non-binary can basically be simplified as a lack of exclusive affinity to male or female. This may be a lack of affinity to either identity (agender), a total affinity to both (bi-gender/), a balanced affinity to both (androgyne), an affinity that changes from day to day (genderfluid), a partial affinity (demigender), or even an affinity to the entire gender spectrum at once (pangender).

It could be an affinity to some aspects of a gender but not others. For example, a demigirl could be someone assigned female at birth who only feels a partial connection to womanhood and femininity, or may be a male-assigned individual who is taking hormone therapy to relieve physical dysphoria, and has a female phenotype, but does not experience a strong connection to the social aspects of womanhood.

In generalist terms, this book will be describing gender in a sense of binary identities (male/female) vs non-binary identities, but this is purely for the sake of writing simplicity. Please know that the depth of gender experience and expression is far, far more complicated than this simple breakdown.

Cog

Cog

Darkly Dai (Now with added werewolf)

Darkly Dai (Now with added werewolf)