A Brief History of Gender Dysphoria

In 1948, noted sexologist Dr. Alfred Kinsey (yes, that Kinsey) was contacted by a woman whose male child adamantly insisted that they were in fact a girl, and that something had gone very wrong. The mother, rather than trying to suppress her daughter, wished to help her become who she knew herself to be. Kinsey reached out to a German endocrinologist named Dr. Harry Benjamin to see if he could help the child. Dr. Benjamin then developed a protocol of estrogen therapy for the teen, and worked with the family to find surgical help.

Benjamin then went on to refine his protocol and treated thousands of patients with similar feelings over the course of his career. He refused to take payment for his work, instead taking satisfaction from the relief he granted these patients, and using their treatment to further his understanding of the condition. He coined a term for this feeling of incongruence in 1973: gender dysphoria. Unfortunately, this term would not be used in the United States until 2013, with the American Psychiatric Association opting for the term “gender identity disorder” instead.

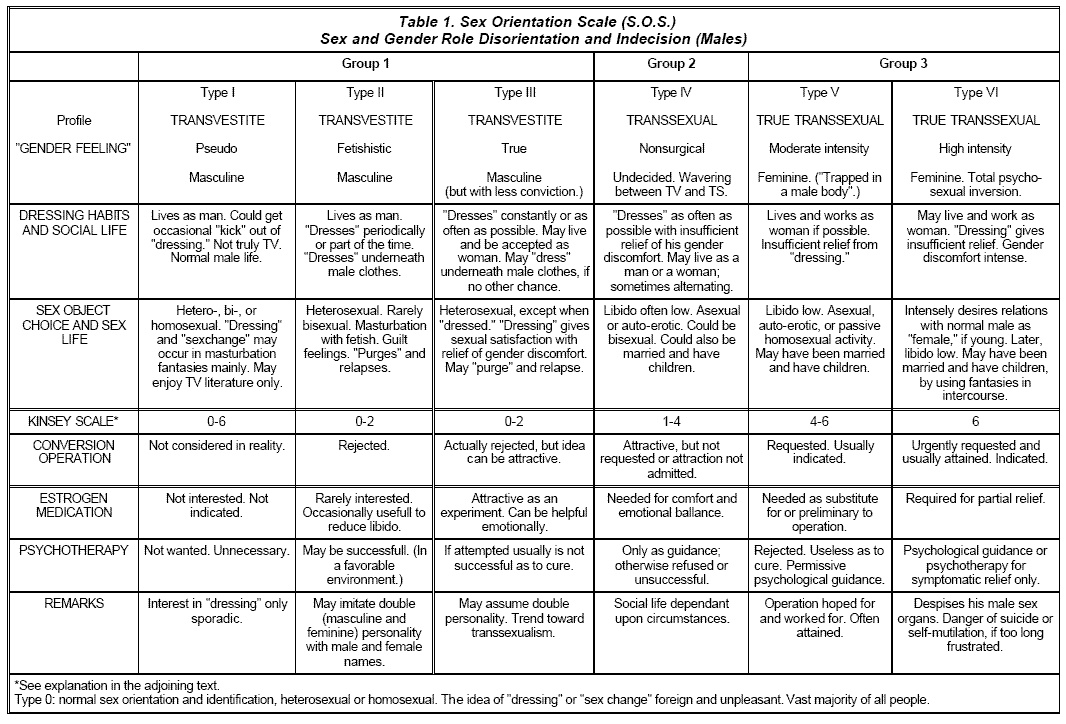

If you are a trans person reading this, you may have heard the name Harry Benjamin before, but probably not in a favorable context. In 1979 his name was used (with permission) in the forming of the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association (HBIGDA), which released a Standards of Care (SoC) for transgender people. This SoC came to be known as the Harry Benjamin Rules, and were infamously limiting in regards to how gender dysphoria could be diagnosed. Patients were placed within a six tier scale based upon their level of misery and sexual dysfunction. If you did not land at Tier 5 or higher, classified as a “True Transsexual”, you were usually rejected for treatment.

The problem was that Tiers 5 and 6 required that you had to be exclusively attracted to your own birth sex. Transition had to be making you straight, not gay, and bisexuals were not allowed. You also had to be experiencing severe distress with your body and genitals and already be living as your true gender without treatment. Many trans people got around these limitations through community coaching and performative presentations, but for many people (myself included) it was believed that, if you did not fit all the criteria, you were not trans enough to transition.

In 2011, the HBIGDA reorganized itself to respond to mounting pressures in trans understanding and acceptance, taking on the new name World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH). Under guidance by actual transgender people (a first for the organization), WPATH then proceeded to release an entirely new Standards of Care (SoC, version 7, the first in ten years) which abandoned the Benjamin Scale, focusing on specific individual symptoms and disconnecting gender from sexuality entirely. Two years later, in 2013, the American Psychiatric Association changed their diagnostic criteria to match the WPATH SoC in their Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) version 5, replacing Gender Identity Disorder with Gender Dysphoria. With this change, medical transition became available to all trans people in the United States.

This is why trans presence across the world has suddenly exploded in the last decade. With easier access comes larger numbers, with larger numbers comes more visibility, with more visibility comes more awareness, and with more awareness comes more people accessing treatment. A study conducted in 2014 showed 0.6% of adults and 0.7% of youth in the United States identified as transgender, a study conducted in 2016 showed 1.8% of high school age students identified as transgender, and a survey conducted by GLAAD in 2017 showed a whopping 12% of respondents 18 to 34 did not identify as cisgender.

Transgender people are coming out of the woodwork; we are everywhere.

So What Is Gender Dysphoria?

Dys·pho·ri·a - Noun

A state of unease or generalized dissatisfaction with life. The opposite of euphoria.

There is a common misconception among both cisgender and transgender people that gender dysphoria refers exclusively to a physical discomfort with ones own body. However, this belief that body discomfort is central to gender dysphoria is in fact a misconception, and is not even a majority component of a gender dysphoria diagnosis. Gender dysphoria crosses a large number of all aspects of life, including how you interact with others, how others interact with you, how you dress, how you behave, how you fit into society, how you perceive the world around you, and, yes, how you relate to your own body. Consequently, proponents of the WPATH SoC 7 and the DSM-5 have taken to a habit of saying that you do not have to have dysphoria to be transgender. This statement is often repeated like a mantra, as it informs people who do not feel significant body discomfort that they may also be transgender.

In principle, gender dysphoria is a feeling of wrongness intrinsic to the self. There is no logical backing to this wrongness; there is nothing which explains it, and you can not describe why you feel this way; it is just there. Things in your existence are incorrect, and even knowing which things are incorrect can be hard to properly identify.

The way I used to describe it is like wearing an adult’s glove when you are a child. You can put your hand into the glove, and your fingers feed into the digits of the glove, but your dexterity with the glove is severely hindered. You might be able to pick something up, but you can not manipulate it like an adult could. Things just aren’t quite right.

Evey Winters described it this way in her Dysphoria post.

Have you ever been sitting somewhere in a public or a formal place and all of a sudden the bottom of your foot itches? It’s not like you can remove your shoes right there and scratch it, so you endure the feeling of dying inside while this itch grows and grows until you are ready to murder the next person that speaks to you.

Or when I was younger I used to watch cable TV in the mornings before school. Because it was cable TV in rural WV in the early 90’s, every so often I’d turn on my favorite channel to watch my shows while I ate my maple oatmeal and I’d be seeing Power Rangers — but the audio would be from another station (usually the weather channel). The video was fine. The audio was fine. But the mismatch between them? That’s the kind of frustration that sits with you all day as a child.

It’s the feeling you get when you ask for a crisp refreshing Diet Coke and the server says, “Is Pepsi ok?”

It is knowing that something is wrong and not being able to do a damn thing about it.

Gender dysphoria is, at its core, simply emotional reactions to the brain knowing that something does not fit. This incongruence is so deep inside the brain’s subsystems that there is no obvious message of what the problem is. The only way we have to identify it is via the emotions that it triggers. Our consciousness receives either positive (euphoria) or negative (dysphoria) feedback according to how well our current environment aligns with our internal sense of self. Part of transition is learning to recognize those signals.

Cisgender people receive them as well, but since the signals usually align with their environment, they take them for granted. There have been a few notable occasions, however, when a cisgender person has been put into a situation where they experience gender dysphoria. Attempts to raise cisgender children as the opposite sex (Content warning: suicide) have always met with failure when the child inevitably declares themselves differently.

These impulses of euphoria and dysphoria, arousal and aversion — they all manifest in many different ways: some obvious, some much more subtle. Dysphoria changes over time as well, taking on new shapes as one moves from pre-awareness into understanding and through transition. The goal of this book is to break down these manifestations into their distinct categories and describe them so that others may learn to recognize them.

However, first I must stress something very important, so important that I am putting it into big bold letters:

EVERY SINGLE TRANS PERSON EXPERIENCES A DIFFERENT SET OF DYSPHORIA SOURCES AND INTENSITIES

There is no one single trans experience; there is no standard set of feelings and discomforts; there is no one true trans narrative. Every trans person experiences dysphoria in their own way to their own degree, and what bothers one person may not bother another.

Okay, with that disclaimer out of the way, let’s get to the meat and potatoes.